In Cuggiono, on the western outskirts of Milan’s province, there is a large mural depicting four mid-20th-century American baseball players.

Anyone passing by this artwork without knowing its history might understandably wonder: What are they doing here? To find out, it’s worth heading to the church of Sant’Ambrogio. But not the one in Milan…

5130 Wilson Avenue, St. Louis, Stati Uniti: St. Ambrose Catholic Church

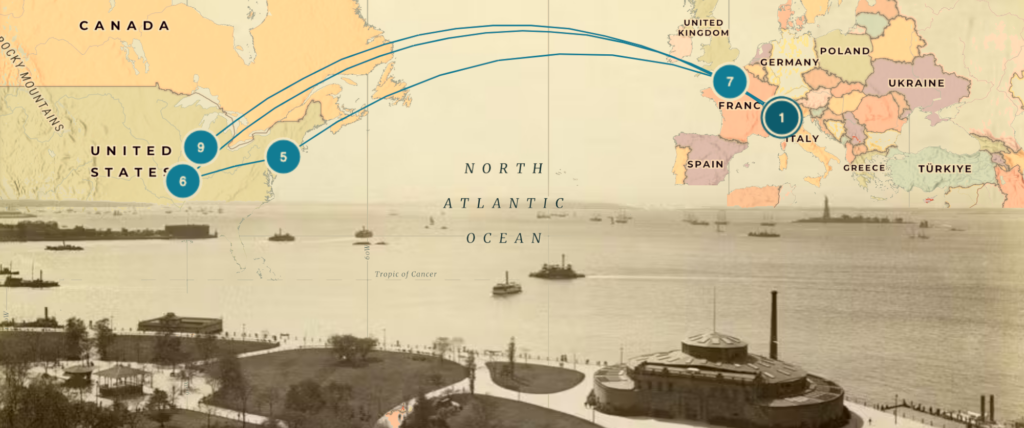

In St. Louis, Missouri, there is a neighborhood called The Hill. It is located a few miles from downtown and, because of its isolation, has retained many of its original features over time. Single-family cottages with manicured lawns line up neatly around the church, significantly dedicated to St. Ambrose, Milan’s patron saint. The Hill for locals is “La Montagna” (the mountain) and is one of the few, true little Italy’s left. It is the neighborhood where, starting in 1880, the first emigrants from Italy-especially from Cuggiono and neighboring towns in the Milan area-went to live, reaching ‘merica. A neighborhood of emigrants, looking for work, hard, in the clay quarries, united by a land of origin and a baggage of traditions around which to feel united. The church of St. Ambrose seems to be the symbol of this glue, built in 1902, destroyed by fire in 1921 and then rebuilt with the labor and money donated by parishioners so that it would continue to be the hub of the community.

However, this cohesion made insertion within American society particularly slow, also complicated by World War I, which reflected on the second generation of Italian-Americans by undermining their relationship with the present and their confidence in the future. La Hill was an Italian working-class neighborhood, with few economic prospects and, as is often the case, destined one day to disperse and mingle, as would happen during the Great Depression to its Polish, Jewish, Irish, German and Italian counterparts in the inner city. But apparently La Montagna did not intend to move.

At the height of Prohibition, in the summer of 1925, Joe Causino, who had been working as recreation director of the Young Men Christian Association (YMCA), arrived on the Hill. The revolution Causino brought revolved around sports and offered neighborhood youth a breath of fresh air. Dozens of clubs sprang up, gyms became a daily meeting place, and Causino was able to obtain several funds for the various teams especially soccer and baseball.

The young men, who had never set foot outside the Hill, finally had the opportunity to broaden their horizons by moving to play against the various Irish, German, Polish, and Hispanic clubs. It was sports and early successes that offered the Italian boys an avenue for integration within American society.

From the Hill to the pitching mound: young Italians conquer baseball

During the years of World War II, Mountain teams began to make a name for themselves especially in baseball, and even more so did some players who had discovered a talent in those teams and on those fields.

In 1943 one Lawrence Peter Berra, better known as Yogi Berra, was signed as a catcher on the New York Yankees baseball team. Drafted, he would shortly leave for war, participate in the Normandy landings, and, once back in America, become one of the most famous players in baseball history. To this day he is considered one of the best catchers who ever lived.

He was born in St. Louis on May 12, 1925, to Pietro Berra and Paolina Longoni, both from Malvaglio, a town bordering Cuggiono (a town Yogi visited in 1959). Yogi Berra was the third American of Italian descent, after Joe Di Maggio and Roy Campanella, to be named to the Hall of Fame in 1972 by the Baseball Association of America. A museum is dedicated to him in the town of Upper Montclair, New Jersey, which holds memorabilia from his career.

The character-characteristic right down to his nickname, which was given to him by a friend who, seeing him sitting cross-legged and arms folded, compared him to yogi one from a movie they had seen together-became famous also for his peculiar “aphorisms,” some of which have become cornerstones of American sports culture and beyond. Among them: It ain’t over ’til it’s over, When you come to a fork in the road, take it, If you don’t know where you’re going, you might end up somewhere else, If the world were perfect, it wouldn’t be, and, rightly, I never said half the things I said.

With such a spirit, it is understandable how his name inspired that of a famous television bear: Yogi Bear.

Another young man of Italian descent, born and raised on the Mountain, trained with Yogi on the neighborhood field. He was Joseph Henry “Joe” Garagiola.

Born in St. Louis on Feb. 12, 1926, to Giovanni Garagiola and Angela Garavaglia, both natives of Inveruno, Joe grew up on Elizabeth Street in the house across the street from Yogi Berra’s, with whom he shared a love of baseball. He was recruited by the St. Louis Cardinals at just 16, favored over his friend Yogi, making his debut in the top division at 20. He looked like a rising star but disappointed expectations as his professional career as a catcher was mediocre. He played only nine seasons with the St. Louis Cardinals, Pittsburgh Pirates, Chicago Cubs and New York Giants, totaling 676 games. But if things did not go as hoped on the field, this only served to bring Joe’s truly great talent into the public eye: in 1960 he brought out the book Baseball is a funny game, which earned him some fame for its humorous character, anecdotes about the sports world, and unique style. He was opening a career of enormous success and notoriety that would last 30 years: within NBC Joe became a phenomenal baseball reporter and commentator. A bit of trivia: Joe Garagiola is often mentioned in the Peanuts strips by Charles M. Schulz.

There are two other Lombard players, born in the same neighborhood and at the same time, portrayed on the Cuggiono mural: Frank Crespi and James Pisoni.

Frank Crespi, between 1938 and 1942, played second base for the St. Louis Cardinals team, becoming in effect the first Hill player to serve in the Major Baseball League and, in 1942, helped the Cardinals win the National League pennant against the New York Yankees. Frank “Creepy” Crespi-so nicknamed from childhood because he was able to run fast while crouched down waiting to catch the ball-was born in St. Louis on Feb. 16, 1918, to Luigi Crespi and Teresa Fumagalli. His father, born in Cuggiono, had emigrated to St. Louis in 1906 at age 15, while his mother, born in Marnate, had joined her brother John in St. Louis in 1913.

World War II, however, brought Frank a considerable load of bad luck as a gift, forever marking the end of his competitive career. Frank did not refuse military service despite having suffered the loss in combat of a brother. During this period Frank injured his leg during a baseball game, a dislocated fracture on which, another accident during a military exercise, recoiled. He then fell out of his wheelchair due to a careless nurse and then, by mistake, was given an overdose of medication that nearly cost him an amputation. Frank recovered but was never able to resume competitive activity. After the end of World War II he remained in baseball for a few years in various capacities but eventually left it. When he died on March 1, 1990, many people discovered for the first time that they were close to a good baseball player, potentially a champion, ruined by the war years.

The fourth Hill baseball player worth mentioning is James Peter Pisoni, born Feb. 14, 1929, in St. Louis. His father Ambrogio Pisoni, born in Buscate, had emigrated to St. Louis aboard the ship Taormina, which arrived in New York on July 10, 1923. He found work in a sewer pipe factory and married Mollie in 1928. James Pisoni studied to become a tool-and-die maker, a worker in the mechanical industry, but a passion for baseball also instilled by his uncle Paul Merlotti took over. At only seventeen he was signed by the St. Louis Browns playing in the American League. At first they had him play in the minor leagues, mostly in the role of center outfielder. He was the last player to make his debut in a Browns jersey before they moved and became the Baltimore Orioles. The last three games against the Chicago Cubs were played in St. Louis. The Browns lost badly but in the second inning of the penultimate game, on September 26, 1953, Pisoni scored the only home run that gave the Browns a temporary lead. In 1954 the Baltimore Orioles traded him to the Kansas City Athletics, later he was a member of the Milwaukee Braves and the New York Yankees. After his retirement he worked as an electrician.

Four faces in black and white along a wall. Four names that sound at once familiar and unusual. To remember four stories of migration that connected a suburban Milanese town to the highest peaks of America’s sports.

January 2025. Editing by tracciaminima by Mattia Gadda, from an article by Ernesto R. Milani.

Sources:

Federazione italiana baseball e softball